While many tests can be used to diagnose epilepsy, the most common is the EEG or electroencephalogram.

On this page, you’ll learn all about EEGs, including the different types of EEGs, how they work, and when one test might be prescribed over another. This page also includes information about the procedure itself, understanding EEG results, and questions to discuss with a doctor before an EEG test.

What is an EEG?

When a seizure occurs, the pattern of the electrical activity (brain waves) changes and the EEG shows the abnormality. An EEG can help identify where the seizure starts, whether it spreads, and what type of seizure it is.

An electroencephalogram (EEG) is a non-invasive diagnostic test used to record brain waves in real time. Diagnosing a person’s specific seizure type(s) can greatly help in selecting the appropriate treatment and understanding what kind of epilepsy one has. This allows doctors to understand the typical brain activity so that they can observe for anomalies, like a seizure.

An electroencephalogram (EEG) is a non-invasive diagnostic test used to record brain waves in real time. Diagnosing a person’s specific seizure type(s) can greatly help in selecting the appropriate treatment and understanding what kind of epilepsy one has. This allows doctors to understand the typical brain activity so that they can observe for anomalies, like a seizure.

Results from an EEG test are used along with the description of the seizure (from a bystander or caregiver who may have witnessed the seizure) and a physical and neurological exam to help a physician identify the seizure type as well as the type of epilepsy or syndrome.

How does an EEG work?

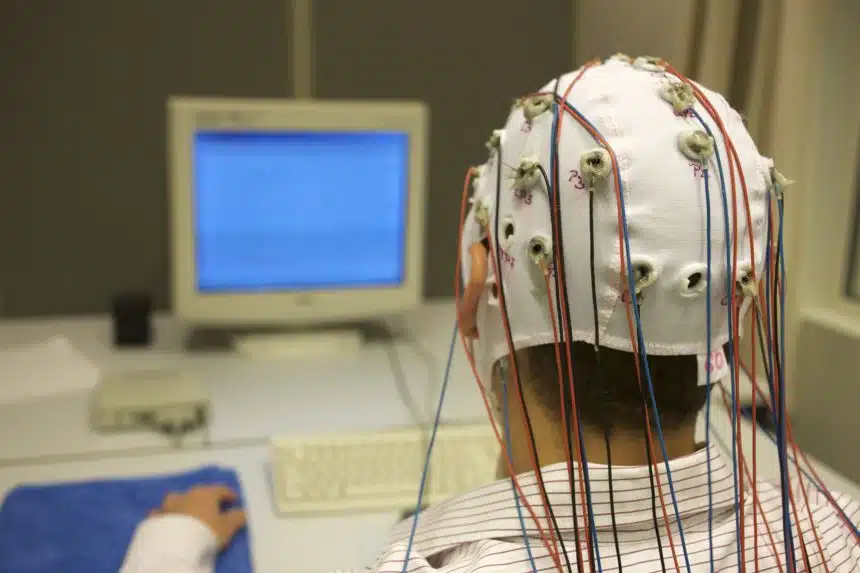

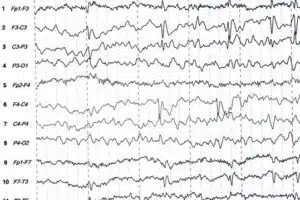

Small discs called “electrodes” are affixed to the scalp, generally between 16 to 25, to monitor and capture electrical activity that is happening in the brain. Signals from the electrodes are amplified and sent to a computer. These brain wave recordings look like wavy lines with peaks and valleys.

Within the squiggly lines that the EEG captures, seizures may appear as very distinct bursts, or small discharges, in the signal, and at other times, the seizures may be more subtle. These bursts or small discharges are referred to as epileptiform discharges. Neurologists and epileptologists are specially trained to read and interpret these signals.

Why is an EEG important for Epilepsy?

EEGs are used for many conditions, including stroke, sleep problems, and dementia, but they have a unique and specific role in diagnosing epilepsy. They can be used when:

- The doctor suspects that the patient is having seizures

- The doctor wants to identify the type of seizure a patient experienced

- The doctor wants to understand what kind of epilepsy the person has. For example, they may want to determine if it is focal epilepsy (where seizures start in one part of the brain) or generalized epilepsy (where seizures start in both halves of the brain)

- The doctor wants to know if the person has seizure triggers

- The doctors want to understand if the seizures are due to epilepsy, or due to some other condition such as non-epileptic seizures (NES)

- The individual is being considered for epilepsy surgery

- The doctor is considering stopping the person’s medication

Is getting an EEG safe?

Getting an EEG is safe. The electrodes only record brainwave activity. Wearing the electrodes may be uncomfortable for some, but the test itself is pain-free.

Because EEGs are non-invasive and pain-free, they can be used at various times, such as when a person is sleeping or even while they’re performing daily activities.

Types of EEG Tests

Routine EEG

A routine EEG is the simplest and quickest form of EEG and is usually the first step in the diagnostic journey for epilepsy.

It can take place at an outpatient clinic which does not require admission into a hospital. This type of EEG will use around 20 electrodes. Generally, it takes between 45 minutes to 2 hours.

High-Density EEG

A high-density EEG (HD-EEG) is like a routine EEG, but the electrodes are placed much closer together. By using more electrodes and placing them close together, there is a higher likelihood that the origin of the seizure can be identified.

HD-EEG may be done when the physician is having trouble figuring out where exactly the seizures are originating from. An HD-EEG may have 64, 128, or 256 electrodes.1 Generally, it takes between 45 minutes to 2 hours.

VIDEO-EEG

A video EEG consists of filming the patient during an EEG. This test is done when it is important to view the patient’s behavior and movements along with their brainwaves. This kind of test is usually done over a long time (hours to days).

SLEEP-DEPRIVED EEG

A sleep-deprived EEG requires a patient to stay awake the night before the test. Sleep deprivation may be used to trigger seizures, which allows doctors to study the brainwaves in real-time. This may be used for some subtle seizure types, such as absence seizures, which may not be accurately captured by the other EEG techniques mentioned above.

AMBULATORY EEG

An ambulatory EEG allows the technician to record brain activity while the patient is at home and able to engage in routine activities. Seizures are very short events, so it is possible (even likely) that the EEG techniques mentioned above may not capture a seizure. Ambulatory EEGs can record for up to 72 hours, which increases the likelihood of seizure activity being recorded.

THE PROCEDURE

An EEG is recommended after a single unprovoked seizure, ideally, soon after the first seizure has occurred.2 The test may be performed in an outpatient setting, at the neurologist’s office, or in an epilepsy monitoring unit (EMU).

The EEG technologist will measure and mark the head to indicate where electrodes will be placed. The electrodes may be attached to the scalp directly or the patient may wear a removable EEG cap. The number of electrodes will depend on the type of EEG being performed.

During the exam, the patient will be asked to lie down and stay still. Throughout the exam, the patient may be asked to open and close their eyes, breathe in and out deeply, or be exposed to other stimuli, such as flashing lights. The EEG will record the patient’s brainwaves, and the machine will trace the readings for the diagnostic team to use.

The length of the exam will depend on the type of EEG being performed, with routine EEGs being the shortest and ambulatory EEGs or video EEGs being the longest.

After the exam, the electrodes are removed, and the scalp may be washed to remove any leftover adhesive. Some patients may experience redness or skin irritation at the site where the electrodes were placed, but it typically resolves within a few hours. The technologist compiles a report which is then analyzed by the neurologist or the epileptologist. Analyzing the test may take some time, and results may be delivered on a return visit.

The absence of “abnormal” brainwaves during the EEG does not mean that the person does not have epilepsy. The physician will use the results of the EEG along with other factors such as symptoms before, during, and after the seizure to make a diagnosis.

THINGS TO TALK ABOUT WITH YOUR DOCTOR BEFORE GETTING AN EEG

The following questions and topics may come in handy when you talk to your doctor about getting an EEG:

- Confirm whether you should stop taking your antiseizure medications (ASMs) before the EEG test

- Confirm how much sleep you should be getting before the EEG

- For a “sleep-deprived” EEG, your physician may request that you stay awake the entirety of the night or most of the night before the procedure

- You may not be able to drive home if you have been given a sedative, so make sure to ask if you should bring someone with you to take you home

- Confirm when you can expect results and if you will discuss them during a follow-up visit

- Discuss what the next steps after the EEG will be

Learn more at our webinar The ABCs of EEGs: An Evolving Tool for Epilepsy Diagnosis.

Related Content

References:

- https://www.cookchildrens.org/services/neurosciences-research/technology/hdeeg/

- Debicki DB. Electroencephalography after a single unprovoked seizure Seizure. 2017 Jul;49:69-73.