< Back to Diagnosing Epilepsy Forward to Treatments and Therapies >

Diagnosing Epilepsy

The first step in this diagnostic journey is to confirm that the person is indeed experiencing epilepsy. Once this is done, the doctor investigates the type of seizures, where they originate in the brain, and whether the seizures are a feature of an epilepsy syndrome.

Getting an epilepsy diagnosis can take time, especially if the seizures are infrequent or are subtle like a staring spell. It is critical to identify the type(s) of seizures one is experiencing to receive an accurate diagnosis.

Getting an accurate diagnosis will guide treatment options and:

- Provide insight into the patient’s long-term prognosis

- Assist in determining if the patient may be a surgical candidate

- Empower the patient in avoiding seizure triggers

The diagnostic process includes tests such as electroencephalogram (EEG), computed tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, and blood tests to investigate genetic mutations.

The process to Diagnose Epilepsy

Seizures can be rare and unpredictable; for many people, it is unlikely that they will have a seizure at their physician’s office during a visit. Sometimes, a person may not even know that they are having seizures,1 or they could have non-epileptic seizures (NES) which may look like a seizure but are not associated with any changes in electrical activity in the brain.

Therefore, the doctor will spend some time and take a detailed medical history and ask questions about what the person was doing and feeling before, during, and after the seizure. The description of the seizure itself is very important, so if a friend or family member witnessed the seizure, bringing them to the visit is helpful. Similarly, if someone took a video of the seizure, showing that to the physician can assist in the diagnosis.

Based on the information that the physician gathers, you may have a conversation about starting an antiseizure medication (ASM) or other treatment. However, in some cases, the physician may need additional information to make a diagnosis and identify the appropriate treatment. Looking at images of the brain and monitoring the electrical activity with long-term video-EEG monitoring at an epilepsy monitoring unit (EMU) may help doctors in diagnosing and treating your epilepsy.

Epilepsy Diagnostic Tests and Tools

Neurological Exams

The doctor may examine a person’s senses, speech, memory, muscle tone, and reflexes to get a better idea of how the person’s seizures are affecting their brain. Neurological tests will usually be done over a period of time to make sure that the ASMs are not adversely affecting brain activity.

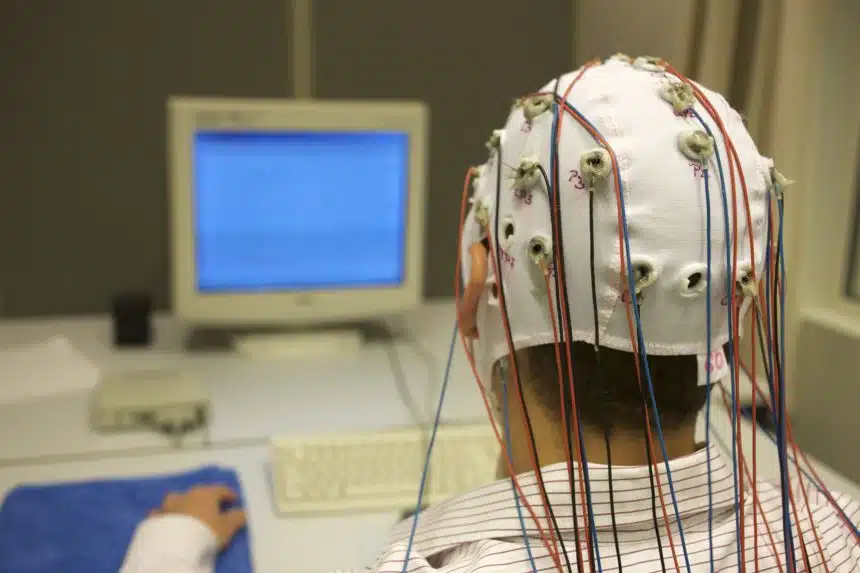

Electroencephalography (EEG)

The electroencephalogram (EEG) is the most common diagnostic test in epilepsy. It is a non-invasive, painless test which monitors the electrical activity in your brain (brain waves). When a patient has a seizure during an EEG, their brain waves change, and the EEG can detect the abnormality. It can help diagnose where the seizure starts, whether it spreads, and what type of seizure it is.

EEGs can take place in the hospital, but sometimes, a physician will order an ambulatory EEG which allows you to go home during the monitoring. For an ambulatory EEG, electrodes from the scalp are attached to wires that end in a small, portable recorder. The patient can wear a cap over the electrodes, go home, and can engage in routine activities while being monitored for up to 72 hours.

If the technologist does not get a good picture of the person’s brainwaves with a routine EEG, the person may be referred to an EMU for more detailed monitoring. A video EEG may be utilized which allows the physician to observe the brain wave patterns from the EEG and see video footage of the patient’s movements and seizures. Patients admitted to the EMU for monitoring, including EEG, are usually there for 3 to 5 days.

Neuropsychological tests

Neuropsychological tests are done by a neuropsychologist, a doctor who specializes in how the brain performs in functions of language, attention, and cognition. Epilepsy can affect your thinking and memory, and neuropsychological tests help understand the extent and impact of these effects.

For a person that is being considered for epilepsy surgery, neuropsychological tests are done to assess thinking, memory, attention, and problem-solving skills.

Computed tomography (CT) scan

Computed tomography (CT) scans are a non-invasive diagnostic tool used to produce images of the brain. The CT machine uses X-rays and a computer to generate a picture of the physical structure of the brain. Using this technique, the physician may be able to see brain tumors or bleeding that could be causing seizures.

CT scans can take place in a hospital or at an outpatient facility. The procedure takes roughly 30 minutes and is conducted by a radiology technician. The patient will lie on a table inside of the CT machine while it takes a series of X-rays around the brain. Then, the computer uses the images from the X-rays to build a detailed picture of the brain.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) creates images or scans of your brain and is used to detect subtle malformations, scar tissue, or damage in the brain that could be contributing to the seizures. MRIs, along with other tests, can be used to pinpoint the diagnosis of a person’s epilepsy and is extremely useful if there is structural damage (or “lesion”) contributing to seizures.

MRIs take place in a hospital or at an outpatient facility. The procedure is conducted by a radiology technician, and the patient will lie on a flat bed that slides inside of the MRI, generally taking between 30 to 60 minutes. MRIs are noisy, so patients may be given earphones to listen to music. A sedative may be helpful for those who are claustrophobic.

Sometimes, a functional MRI (fMRI) may be done. An fMRI is a non-invasive way of mapping the parts of the brain needed for speaking, understanding speech, moving, and sensing. When a neurosurgeon is thinking of resecting (or cutting away) certain areas that are producing seizures, an fMRI may be done so that important areas of the brain are avoided.

An MRI does not expose you to any radiation; however, it is important to let your physician know if you are pregnant.

Genetic Tests

It is estimated that a large percentage of epilepsies are due to genetic factors; however, there are over a thousand genes that have been linked to epilepsy, and we are still identifying more. Changes to some of these identified genes cause epilepsy, while changes to others may just increase the likelihood of developing epilepsy. Therefore, genetic testing may be performed on a patient with epilepsy to determine if there is a genetic variation that could explain their epilepsy.

A blood or saliva sample is taken and DNA analyzed to look for genetic variants known to be associated with epilepsy or epilepsy syndromes.

There are different types of analyses: epilepsy “panel”, the whole-genome, or the whole-exome. The “panel” will look at a specific set of genes that are known to be linked to epilepsy, ranging anywhere from around 20 to 800 genes. 4 Whole-genome sequencing looks at the complete DNA of an individual, so around 3 billion pairs of DNA.5 Exomes are part of the genome (about 2%), so whole-exome sequencing looks only at a small part of the total DNA of an individual.

Many times, blood testing to find genetic causes is done alongside counseling to make sure the patient understands what the results of the genetic tests mean.3

Related Content

References:

- Elger CE, Hoppe C. Diagnostic challenges in epilepsy: seizure under-reporting and seizure detection Lancet Neurol. 2018 Mar;17:279-288.

- Hampel KG, Garces-Sanchez M, Gomez-Ibanez A, Palanca-Camara M, Villanueva V. [Diagnostic challenges in epilepsy] Rev Neurol. 2019 Mar 16;68:255-263

- Poduri A. When Should Genetic Testing Be Performed in Epilepsy Patients? Epilepsy Curr. 2017 Jan-Feb;17:16-22

- https://www.labcorp.com/tests/630268/comprehensive-epilepsy-ngs-panel

- https://www.raregenomics.org/faq#:~:text=What%20is%20the%20difference%20between,complete%20DNA%20of%20an%20organism.&text=The%20exome%20makes%20up%20only,are%20found%20in%20the%20exome