< Back to Epilepsy Basics Forward to Diagnosing Epilepsy >

Table of Contents:

- What is a seizure?

- The relationship between seizures and epilepsy

- What causes a seizure?

- What are the different types of seizure?

- Symptoms of seizures

- Diagnosing seizures

- Treatment options for seizures

- FAQ

What is a Seizure?

A seizure is an electrical disturbance in the brain that interferes with its normal function. Many scientists and clinicians compare it to an “electrical storm in the brain” in which your brain cells hyper-synchronize in an abnormal pattern, disrupting that delicate brain signal balance.

Seizures vary from person to person, depending upon their seizure type. That’s because epilepsy is a spectrum disorder, meaning the causes, type, and severity can differ greatly amongst those affected by it. [1] Some people have visible symptoms, such as a tonic-clonic seizure (previously called grand-mal), and others may have no visible symptoms, such as absence seizures (previously called petit mal).

Relationship between Seizures and Epilepsy

Epilepsy is characterized by recurrent seizures, but not all seizures indicate epilepsy. Understanding the relationship between seizures and epilepsy is crucial for accurate diagnosis and treatment.

In the words of Dr. Robert S. Fisher, “A seizure is the event…whereas epilepsy is the condition of seizures that spontaneously come back on their own.” Therefore, it’s possible to experience a seizure (such as a febrile seizure) and not have epilepsy. A person is considered to have epilepsy if they have two or more unprovoked seizures more than 24 hours apart or if they have one seizure with a probability of having future seizures.

What Causes a Seizure?

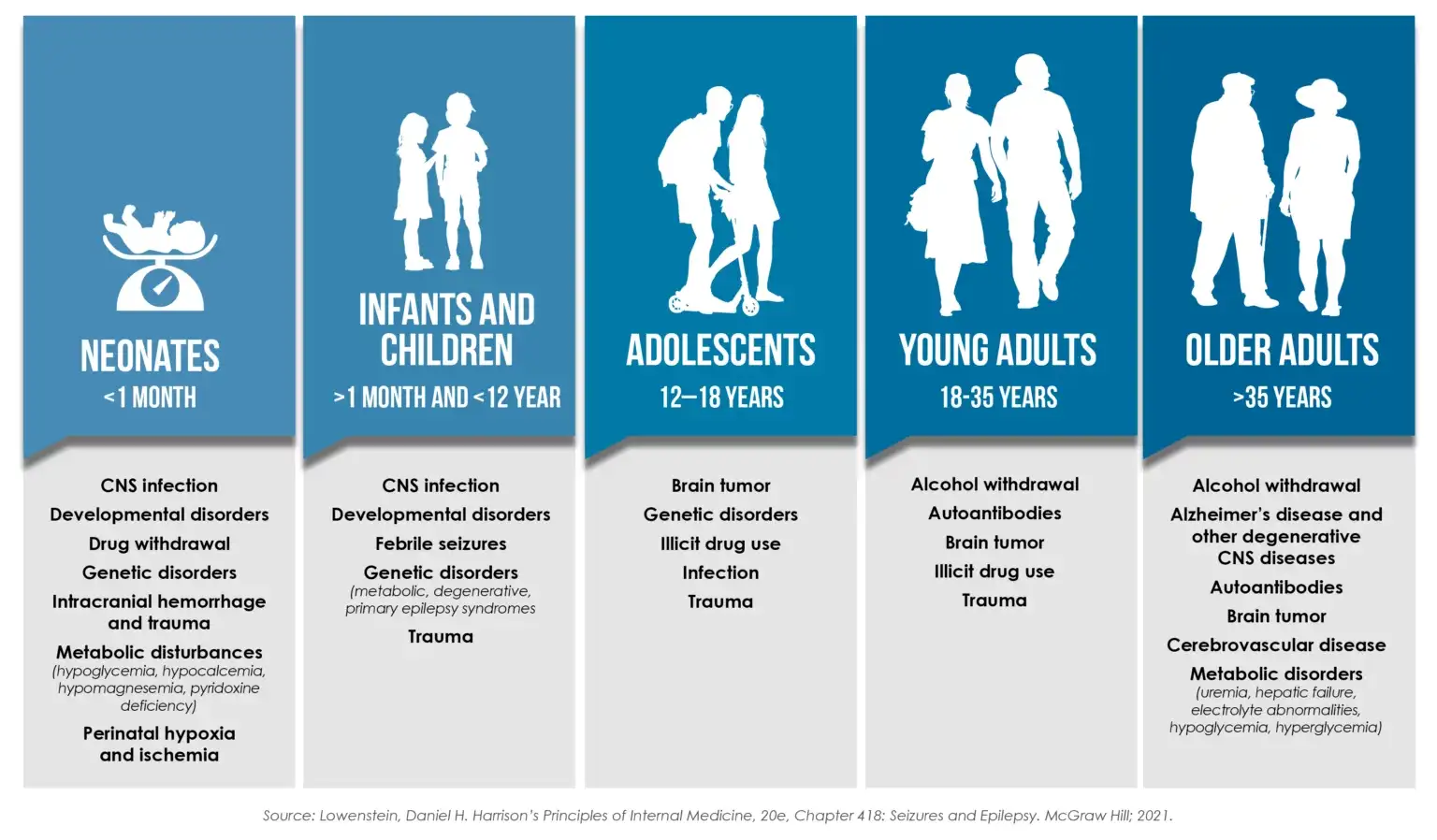

The underlying causes of seizures are complex. Seizures can develop from a range of events, from faulty wiring during brain development to brain inflammation, or from physical injuries or infections. [2]

Epilepsy is the most common cause of seizures, but other factors such as head injuries, infections, brain tumors, and genetic disorders can also trigger them. Unfortunately, in 50% of cases, the cause is unknown.

Certain events or situations may increase the likelihood of a seizure occurring in people with epilepsy; these are called seizure triggers. Some common triggers include:

- Use of alcohol or drugs

- Flashing lights

- Stress

- Not getting enough sleep

- Certain types of foods, caffeine

- Changes in blood sugar

- Common cold, flu, or other illness

- Menstruation

- Not taking medication

- Triggers vary from person to person, and an individual may have multiple triggers.

Causes of seizures by age

What are the different types of Seizure?

There are several different types of seizures, each with its own distinct characteristics and symptoms. When identifying seizure types, they are first grouped into one of two broad categories – focal onset and generalized onset – based on where they start in the brain.

Your brain has two hemispheres, or halves: the left hemisphere and the right hemisphere. The hemispheres are separated by a fissure – a deep groove. The sides can communicate with each other because they are connected by the corpus callosum, a large bundle of nerve fibers.

Focal seizures start on and only involve one hemisphere of the brain.

Generalized seizures, on the other hand, involve both hemispheres. Sometimes, the onset (where the seizure starts) may be unknown.[3]

It is possible for a seizure to start on one side of the brain and then spread to the other side. When this happens, it is referred to as a focal to bilateral seizure.

Learn more about the different types of seizures

Symptoms of Seizures

The signs and symptoms of a seizure will vary from person to person, as well as the type, severity, and phase of the seizure. General signs and symptoms can include:

- Unusual behaviors/sensations

- Uncontrollable movements

- Loss of consciousness

It’s important to remember that some seizures are visible to others, whereas others are not. Most seizures last between 30 seconds and 2 minutes; if a seizure lasts longer than 5 minutes, you should seek medical care immediately.

Diagnosing Seizures

Diagnosing seizures involves a comprehensive evaluation to identify the underlying cause and determine the most suitable treatment approach.

Medical History and Physical Examination

A thorough medical history and physical examination are essential for assessing the patient’s overall health and identifying any potential triggers or risk factors for seizures.

EEG (Electroencephalogram)

An EEG is a diagnostic test that records the brain’s electrical activity, helping healthcare professionals detect abnormal patterns associated with seizures and epilepsy.

Imaging Tests

Imaging tests such as MRI or CT scans may be performed to visualize the brain’s structure and identify any abnormalities or lesions that could be causing seizures.

Treatment Options for Seizures

Effective management of seizures often involves a combination of medication, lifestyle modifications, and, in some cases, surgical intervention.

Medications for Seizures

Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are commonly prescribed to control seizures by stabilizing electrical activity in the brain and preventing recurrent episodes.

Surgery for Seizures

Surgical procedures may be recommended for individuals whose seizures are resistant to medication or when a specific area of the brain is identified as the source of seizures.

Dietary Therapy for Seizures

Certain diets, such as the ketogenic diet, have been shown to be effective in reducing seizure frequency, particularly in children with epilepsy.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

-

Can seizures be fatal?

Seizures themselves are not typically fatal, but certain complications or underlying conditions associated with seizures can be life-threatening.

-

Are all seizures caused by epilepsy?

No, while epilepsy is a common cause of seizures, there are various other factors and conditions that can trigger seizures, such as brain injuries, infections, and genetic disorders.

-

Can seizures be prevented?

While it may not be possible to prevent all seizures, certain lifestyle modifications, medication adherence, and avoiding known triggers can help reduce the risk of seizure occurrence.

-

How do I help someone having a seizure?

If you witness someone having a seizure, stay calm, ensure their safety by removing nearby hazards, cushion their head, and time the seizure. Do not restrain them or put anything in their mouth.

-

Is it safe for someone with seizures to drive?

Driving regulations vary depending on the severity and frequency of seizures, as well as local laws. It’s essential for individuals with seizures to consult with their healthcare provider and adhere to any driving restrictions or guidelines in place.

Related Content

References:

- Sirven JI. Epilepsy: A Spectrum Disorder Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2015 Sep 1;5:a022848.

- Simon D. Shorvon FA, Renzo Guerrini. The Causes of Epilepsy: Common and Uncommon Causes in Adults and Children: Cambridge University Press; 2011.

- Fisher RS, Cross JH, D’Souza C, French JA, Haut SR, Higurashi N, et al. Instruction manual for the ILAE 2017 operational classification of seizure types Epilepsia. 2017 Apr;58:531-542.