< Back to Epilepsy Basics Forward to Diagnosing Epilepsy >

Table of Contents:

- Understanding Epilepsy Basics

- What causes epilepsy?

- How common is epilepsy?

- How is epilepsy treated?

- How is epilepsy diagnosed?

- FAQs

Understanding Epilepsy Basics

Epilepsy is a neurological disorder characterized by recurrent seizures. It affects people of all ages and can significantly impact daily life. Understanding epilepsy is crucial for proper management and support.

Types of Epilepsy

Epilepsy manifests in various forms, classified based on seizure type and underlying cause:

- Generalized Epilepsy: Affects both hemispheres of the brain, resulting in widespread symptoms like convulsions or absence seizures.

- Focal Epilepsy: Limited to one area of the brain, often causing localized symptoms, such as sensory changes or motor disruptions.

- Unknown Epilepsy: When the root cause of seizures cannot be determined, this classification is used.

Seizures and Epilepsy

When it comes to understanding neurological conditions, terms like “seizures” and “epilepsy” are often used interchangeably. However, these are distinct concepts, each with unique characteristics and implications.

When a person has had two or more seizures more than twenty-four hours apart that have not been provoked by specific events such as a stroke, brain injury, infection, fever, or fluctuations in blood sugar, they are considered to have epilepsy.

A person can also be diagnosed with epilepsy if they have one or more unprovoked seizures and a probability of future seizures.

Understanding Seizures

A seizure is an electrical disturbance in the brain that interferes with its normal function. Many scientists and clinicians compare it to an “electrical storm in the brain” in which your brain cells hyper-synchronize in an abnormal pattern, disrupting that delicate brain signal balance.

Seizures vary from person-to-person, depending upon their seizure type. That’s because epilepsy is a spectrum disorder, meaning the causes, type, and severity can differ greatly amongst those affected by it.

Common types of seizures include:

- tonic-clonic seizure (previously called grand-mal)

- absence seizures (previously called petit mal)

- febrile seizures

- focal seizures

Learn more about the types of seizures.

What causes Epilepsy?

While the exact causes of epilepsy are varied and not entirely known, in general epilepsy and seizures result from abnormal signals from neurons (a type of brain cell) in the brain. It can be genetic, meaning it is the result of mutations in a person’s genes, or it can be acquired through events such as physical injury or infection[1]. In up to 50% of epilepsy cases worldwide, the cause is idiopathic, which means unknown.

Some underlying causes of acquired epilepsy include:

- Brain structure abnormalities

- Head trauma

- Infectious disease

- Stroke

- Tumors

How common is Epilepsy?

Epilepsy is more common than many people realize. It’s estimated that approximately 1 in 26 people will develop epilepsy at some point in their lives. This means that millions of individuals worldwide are affected by epilepsy, regardless of age, gender, or background. While the frequency of epilepsy varies depending on factors such as age group and geographic region, it is considered one of the most prevalent neurological disorders globally. Despite its prevalence, there is still a need for greater awareness, understanding, and support for individuals living with epilepsy and their families.

Epilepsy in Children

Children with epilepsy face unique challenges, as seizures can affect development and school performance.

- Academic Support: Teachers and peers should be informed about the condition to provide necessary support.

- Behavioral Therapy: Helps children adapt and manage emotional responses.

- Family Counseling: Assists families in understanding epilepsy and coping with its impacts.

Does Age Impact Epilepsy?

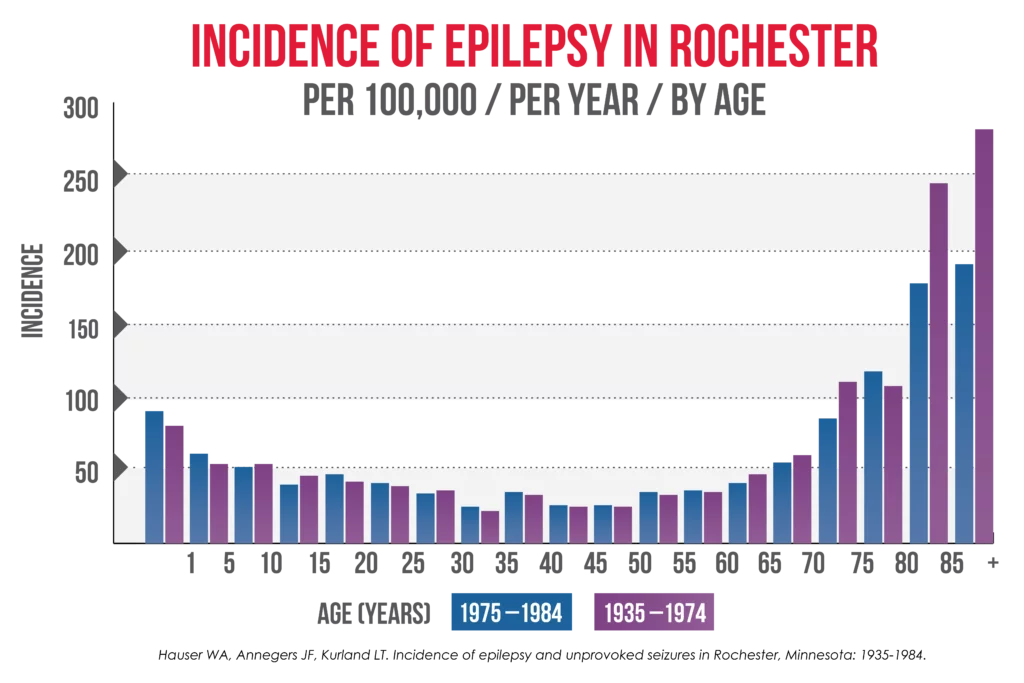

While epilepsy and seizures can develop in any person at any age, new cases are most common in children, especially in their early years of life. The incidence of epilepsy lessens after childhood but then increases again in older adults (>60 years of age).

Infants in their first year of life are vulnerable to seizures (and epilepsy) because their brains are rapidly developing, with neurons growing and making new connections all the time. For many infants, their brains will develop without disruption; for others, however, they may experience disturbances that can cause epilepsy. This may include head trauma, genetic mutation, or viral infection in the birthing parent during pregnancy.

Neonatal seizures (seizures during the first four weeks of a baby’s life) may be difficult to diagnose because they are subtle and resemble normal movements of a baby, or because some doctors do not have specialized training in epilepsy. A pediatric neurologist can help diagnose neonatal seizures and identify their cause.

Though incidence begins to decrease as an infant’s brain continues to develop, toddlers and young children also develop epilepsy. Most commonly, this age group is susceptible to febrile seizures (seizures associated with fever), but epilepsy can develop from genetic disorders, central nervous system (CNS) infections, developmental disorders, and head trauma.

The incidence of epilepsy decreases during the teenage, early adult, and middle-aged years but then rises again in adults 60 years of age and older. In this age range, epilepsy can be associated with strokes, Alzheimer’s disease, head trauma, and brain tumors, among other things.

Does Race and Ethnicity Impact Epilepsy?

There is limited research available on the incidence of epilepsy across race and ethnicity. There is no direct evidence that a person’s race or ethnicity alone puts them at a higher risk for developing epilepsy; however, there is research to suggest that there are commonalities between people with similar socioeconomic, racial, or ethnic backgrounds.

The prevalence of active epilepsy was found to be higher in non-Hispanic White Americans and non-Hispanic Black Americans, as compared to Hispanic Americans.[7] The prevalence of active epilepsy was higher in Black Americans as compared to White Americans.[8]

The proportion of people with “unclassifiable” epilepsy was found to be higher in people with African ancestry as compared to whites. The latter finding may be due to the lack of access to diagnostic testing, such as prolonged EEG monitoring, making diagnosis difficult and uncertain.[9]

It is estimated that 1.5% of Asian Americans are living with epilepsy, though more research is needed.[10]

It’s important to note that there are disparities in epilepsy care, both in the United States and abroad, which can result in certain ethnicities and races being over or underreported in epilepsy research. This is known as the treatment gap or the mismatch between those who need treatment and those who have access to treatment.

How is Epilepsy Treated?

When treating epilepsy, patients are prescribed treatment based on the type or types of seizures they are experiencing. A variety of treatments are available, including medication, dietary changes, devices, and surgery. While the goal of epilepsy treatments is straightforward—no seizures, no side effects—finding the right treatment plan may require trial and error.

Usually, newly diagnosed people with epilepsy will start an oral medication that is appropriate for their diagnosis. If the first drug treatment does not stop their seizures, their neurologist will work with the patient to try other medications, or a combination thereof, as well as evaluate if they are a potential candidate for surgery.

While there are many medications, medical devices, and surgical options to treat epilepsy, right now, there are no known cures for epilepsy. However, incredible advancements in research have helped us understand the mechanisms that cause seizures better than at any other point in history. That’s why we must invest in research – to understand the underlying causes of epilepsies – so we can cure them.

Living with Epilepsy

Living with epilepsy requires careful management of triggers, adherence to medication regimens, and awareness of safety precautions. Building a strong support network and staying informed about the condition can help individuals lead fulfilling lives despite the challenges posed by epilepsy.

How is Epilepsy Diagnosed?

When diagnosing epilepsy, medical professionals conduct tests to detect abnormalities in a patient’s brainwaves. Tests can also detect seizure activity, including where in the brain a seizure starts. The most common diagnostic test for epilepsy is the EEG, but other brain scans, like MRI or PET, can also be used depending on the patient’s seizure or epilepsy type (or both). To determine if a patient does (or does not) have epilepsy, their healthcare provider compares their test results to the guidelines and criteria established by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

-

What are the common signs of epilepsy?

Common signs of epilepsy include seizures, which can manifest as convulsions, staring spells, or temporary confusion.

-

Can epilepsy be cured?

Epilepsy can often be managed with medications, lifestyle modifications, and other therapies. However, there is currently no cure. That’s why we must invest in research – to understand the underlying causes of epilepsy – so we can advance science towards a cure.

-

Is epilepsy hereditary?

While genetics can play a role in some cases of epilepsy, not all forms of the condition are hereditary. Environmental factors and other variables also contribute to the risk of developing epilepsy.

-

How does epilepsy affect daily life?

Epilepsy can impact daily life in various ways, including limitations on activities, driving restrictions, and the need for medication management. However, many individuals with epilepsy lead productive and fulfilling lives with proper management.

-

What should I do if someone has a seizure?

If someone is having a seizure, stay calm and ensure their safety by removing any nearby hazards. Do not restrain them or put anything in their mouth. Once the seizure has ended, offer reassurance and support as needed and seek medical attention if necessary.

-

What does epilepsy mean?

Epilepsy is a neurological disorder characterized by recurrent, unprovoked seizures resulting from abnormal electrical activity in the brain. It affects people of all ages and can vary widely in terms of severity and symptoms. Epilepsy is a chronic condition, meaning it usually requires ongoing management and treatment to control seizures and improve quality of life.

-

What is seizure-prone illness?

A seizure-prone illness refers to a condition that makes an individual more susceptible to experiencing seizures. This can include conditions like epilepsy, but also certain infections, brain injuries, or metabolic imbalances that temporarily or permanently increase seizure risk. People with seizure-prone illnesses may need specialized treatment to manage their condition and prevent seizures from occurring.

-

What is the difference between a seizure and epilepsy?

A seizure is a single event of abnormal electrical activity in the brain, which can happen to anyone under certain circumstances, such as fever, head injury, or infection. Epilepsy, on the other hand, is a chronic disorder where a person experiences recurrent, unprovoked seizures over time. While anyone can have a seizure, having multiple unprovoked seizures is generally required for a diagnosis of epilepsy.

-

What is the definition of epilepsy?

Epilepsy is defined as a neurological disease marked by two or more unprovoked seizures that occur more than 24 hours apart. It is considered a chronic disorder, with varying types and severities of seizures, and can have diverse underlying causes. Epilepsy is managed through treatments like anti-seizure medications, lifestyle adjustments, and, in some cases, surgical interventions to help control seizure activity.

References

- Epilepsy Available at: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/epilepsy.

- GBD 2016 Epilepsy Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of epilepsy, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019; 18(4):P357-375.

- https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laneur/article/PIIS1474-4422(18)30454-X/fulltext

- Simon D. Shorvon FA, Renzo Guerrini. The Causes of Epilepsy: Common and Uncommon Causes in Adults and Children: Cambridge University Press; 2011

- https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/epilepsy-a-public-health-imperative

- Hirtz D, Thurman DJ, Gwinn-Hardy K, Mohamed M, Chaudhuri AR, Zalutsky R. How common are the “common” neurologic disorders? Neurology. 2007 Jan 30;68:326-337.

- Aaberg KM, Gunnes N, Bakken IJ, Lund Søraas C, Berntsen A, Magnus P, et al. Incidence and Prevalence of Childhood Epilepsy: A Nationwide Cohort Study Pediatrics. 2017 May;139.

- QuickStats: Age-Adjusted Percentages of Adults Aged ?18 Years Who Have Epilepsy, by Epilepsy Status and Race/Ethnicity — National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2010 and 2013 Combined. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm6523a8.htm#:~:text=The%20prevalence%20of%20epilepsy%20and,and%200.6%25%2C%20respectively.

- Kroner BL, Fahimi M, Kenyon A, Thurman DJ, Gaillard WD. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in epilepsy in the District of Columbia Epilepsy research. 2013;103:279-287.

- Friedman D, Fahlstrom R, Investigators E. Racial and ethnic differences in epilepsy classification among probands in the Epilepsy Phenome/Genome Project (EPGP) Epilepsy research. 2013;107:306-310.

- Epilepsy Foundation. 2014. Epilepsy and Asian Americans. [online] Available at: https://www.epilepsy.com/living-epilepsy/epilepsy-and/asian-americans [Accessed 15 December 2021].