What is Post-Traumatic Epilepsy (PTE)?

Post-traumatic epilepsy or PTE is defined as a recurrent seizure disorder that occurs following a traumatic brain injury or TBI.1 PTE is unpredictable. It can take weeks or even years for PTE to develop following a TBI.

What causes Post-Traumatic Epilepsy (PTE)?

TBI may be caused by different kinds of injuries, including mild, moderate, or severe blows to the head, blasts, or penetrating injuries.2 Some examples of what might cause this type of injury include an accidental fall, a motor vehicle accident, or a sports-related injury, to name a few.3

Who is at risk for PTE?

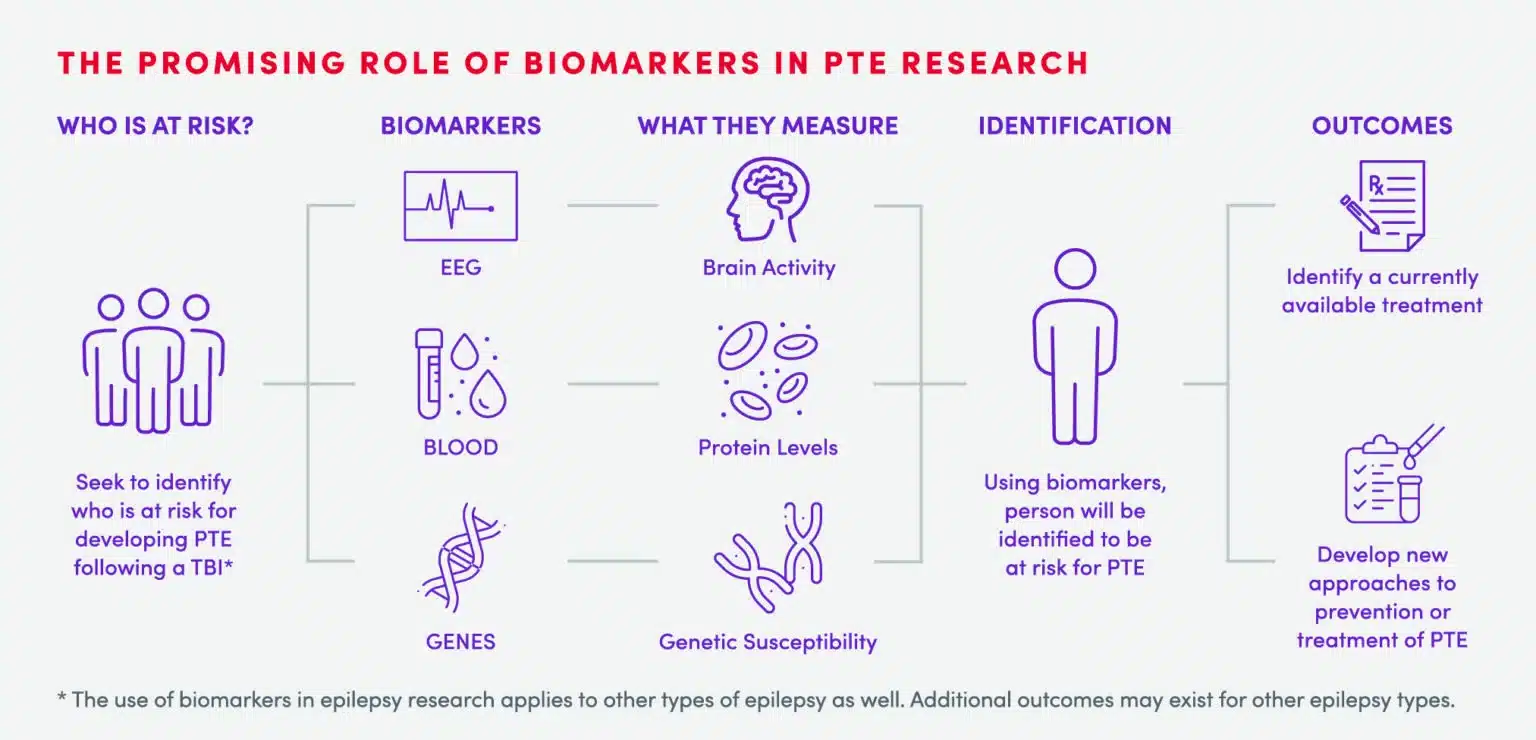

While not all TBI become PTE, both severe, as well as mild TBI, can increase the risk of developing PTE.4-7 While individuals who serve in the military may be especially susceptible to developing PTE, any TBI can put a person at risk for developing PTE.3 Currently, however, it is not possible to predict who will go on to develop PTE from TBI.

Treatment options for Post Traumatic Epilepsy

Currently, there is no known treatment for PTE following TBI. What we do know is that to develop effective therapies, we need strategies to allow us to understand who is at risk for developing PTE as well as an understanding of the changes that happen in the brain before PTE develops. To do this, we need more research so that we can begin working to prevent PTE in patients with TBI. This is why we created the CURE Epilepsy PTE Initiative, with a $10 million grant from the Department of Defense.

PTE Resources

Preventing Post-Traumatic Epilepsy with 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose Treatment: This CURE Epilepsy Discovery shows a promising advance in the quest to prevent post-traumatic epilepsy. Dr. Thomas Sutula from the University of Wisconsin and his team have found that the administration of 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose (2DG) following a traumatic brain injury can significantly reduce the subsequent development of post-traumatic epilepsy in a rodent model. Learn More

CURE Epilepsy PTE Initiative: CURE Epilepsy’s collaborative, multi-investigator PTE research program aims to develop better models to study PTE and discover methods to predict who is at risk as a way to intervene early and prevent PTE. Learn More

Preventing Post-Traumatic Epilepsy May be Possible by Inhibiting Two Inflammation-Based Signaling Pathways: This CURE Epilepsy Discovery involves research to assess what happens in the brain after TBI, which is crucial to discovering possible therapeutic options to prevent epilepsy from developing. Data from this CURE Epilepsy Discovery further validate the roles of HMGB1, its receptors TLR4 and RAGE, and their downstream inflammatory pathways in the PTE process itself, including cellular level changes, and how blocking either of these pathways may one day prevent PTE. Read Discovery

Post-Traumatic Epilepsy and Cognitive Training: Improving Quality of Life Through HOBSCOTCH: This webinar provides an overview of PTE and cognitive dysfunction, as well as some strategies to help improve the quality of life of those with PTE and their caregivers. The webinar also provides details about HOBSCOTCH (Home Based Self-Management and Cognitive Training Changes Lives), a behavioral program designed to address memory and attention problems in adults with epilepsy and discuss a clinical trial opportunity for veterans and civilians living with PTE. Watch

Post-Traumatic Epilepsy (PTE): This webinar reviews efforts underway to advance our understanding of PTE, as well as the exciting new therapies being developed that may one day result in a cure. Watch

Related Content

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

-

What is post-traumatic epilepsy (PTE)?

Post-traumatic epilepsy (PTE) is defined as a recurrent seizure disorder that occurs following a traumatic brain injury (TBI).1

-

Who is susceptible to PTE?

While individuals who serve in the military may be especially susceptible to developing PTE, any TBI – for example, by accidental fall, motor vehicle accident or sports-related injury – can put a person at risk for developing PTE.3

-

What type of TBI increases the risk of PTE?

Both severe as well as mild TBI can increase the risk for developing PTE.4-7

-

What causes traumatic brain injury (TBI)?

TBI may be caused by different kinds of injuries including mild, moderate or severe blows to the head, blasts or penetrating injuries.2

-

How many US military personnel were diagnosed with TBI from 2010-2019?

Nearly 500,000 US Military personnel were diagnosed with TBI from 2000-2023.8

-

What is the correlation between TBI and developing epilepsy?

A reported 53% of a group of Vietnam veterans who suffered from severe TBI in the form of penetrating brain wounds subsequently developed epilepsy.9

-

What is the likelihood of developing epilepsy from experiencing a TBI?

Military veterans of wars in Afghanistan and Iraq who experienced TBI had 19x greater odds of developing epilepsy than those without TBI.4

-

Can you prevent PTE following TBI?

Currently, there is no known prevention for PTE following TBI. Treatments for PTE may be only partially effective and can have significant side effects.9

-

How many people in the US are effected by TBI?

In 2014, there were approximately 2.87 million TBI-related emergency department visits, hospitalizations and deaths in the United States. The number of total events increased by 53% from 2006 (approximately 1.88 million) to 2014 (approximately 2.88 million).11

Our Areas of Focus

Since its inception, CURE Epilepsy has been at the forefront of epilepsy research, raising over $100 million to fund research and other programs that will lead the way to a cure for epilepsy.

See our other Focus Areasraised to fund research and other programs that will lead the way to a cure for epilepsy.

References

1. Pitkänen A and Bolkvadze T. Head Trauma and Epilepsy. Jasper’s Basic Mechanisms of the Epilepsies [Internet] 4th Edition 2012. Noebels JL, Avoli M, Rogawski MA, et al., editors.

2. Marr A, Coronado V, editors. Central Nervous System Injury Surveillance: Annual Data Submission Standards for the Year 2002. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2004.

3. Annegers JF and Coan SP. The risks of epilepsy after traumatic brain injury. Seizure 2000, 9(7):453-457.

4. Pugh, M.J., Orman, J.A., Jaramilo, C.A., Salinsky, M.C., Towne, A.R., Amuan, M.E., Roman, G., McNamee, S.D., Kent, T.A., McMillan, K.K., Hamid, H., and Grafman, J.H. (2015). The prevalence of epilepsy and association with traumatic brain injury in veterans of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars. Head Trauma Rehabil 30, 29–37.

5. Annegers, J.F., Rocca, W.A., and Hauser, W.A. (1996). Causes of epilepsy: contributions of the Rochester epidemiology project. Mayo Clin. Proc 71, 570–575.

6. Hauser, W.A., Annegers, J.F., and Kurland, L.T. (1993). Incidence of epilepsy and unprovoked seizures in Rochester, Minnesota: 1935–1984. Epilepsia 34, 453–468.

7. Temkin N. Preventing and treating posttraumatic seizures: The human experience. Epilepsia 2009, 50(Suppl. 2): 10–13

8. Mil: The Official Website of the Military Health System. DoD TBI Worldwide Numbers. [Online] https://www.health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Centers-of-Excellence/Traumatic-Brain-Injury-Center-of-Excellence/DOD-TBI-Worldwide-Numbers.

9. Salazar AM, Jabbari B, Vance SC, Grafman J, Amin D, Dillon JD. Epilepsy after penetrating head injury. I. Clinical correlates: a report of the Vietnam Head Injury Study. Neurology 1985; 35(10): 1406-1414.

10. Szaflarski JP, Nazzal Y, Dreer LE. Post-traumatic epilepsy: Current and emergent treatment options. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2014; 10:1469-1477.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019). Surveillance Report of Traumatic Brain Injury-related Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths—United States, 2014.